In 1916, Dr. E.B. Cragin delivered an address entitled "Conservatism in Obstetrics" to the Eastern Medical Society of New York in which he coined the phrase "Once a caesarean, always a caesarean."

For most of the twentieth century, doctors followed this dogma believing that once a woman delivered by C/S she should deliver all future pregnancies by repeat C/S. Clinical studies starting the 1960s, however, concluded that this practice was not always necessary.

In 1980, the National Institutes of Health (NIH) Consensus Development Conference Panel questioned the necessity of routine repeat Cesarean Section. After extensive research, the panel made recommendations regarding the VBAC. Their recommendations gave support to the practice of the TOLAC and successful VBAC with a significant rise in the number of attempted VBAC from the 1980s through 1996.

A major turning point occurred in 1996 with a study published in The New England Journal of Medicine (MacMahon et al, 1996) which concluded that a vaginal delivery after previous C/S (VBAC) was associated with an increased maternal complications as compared to the Elective Repeat Cesarean Section (ERCS).

The American College of Obstetrics and Gynecology (ACOG) subsequently issued guidelines in its 1999 Practice Bulletin which recommended that "VBAC should be attempted in institutions equipped to respond to emergencies with physicians immediately available to provide emergency care." (ACOG, 1999) This practice bulletin also recommended that a physician "capable of monitoring labor and performing an emergency cesarean delivery" be "immediately available throughout active labor," and that anesthesia and personnel for an emergency cesarean be "available."

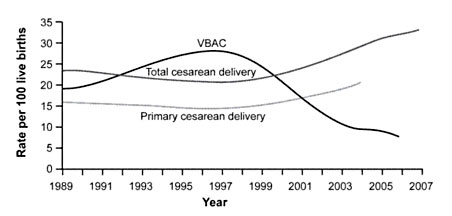

Logistical and professional liability issues led many hospitals to restrict or prohibit the practice of VBAC. As a result, the rate at which VBAC was attempted fell from 26% in the early 1990s to less than 10% today.

Figure 1. Rates of Total Cesarean Deliveries, Primary Cesarean Deliveries, and Vaginal Birth After Cesarean (VBAC), 1989 to 2007. Data from the National Center for Health Statistics.

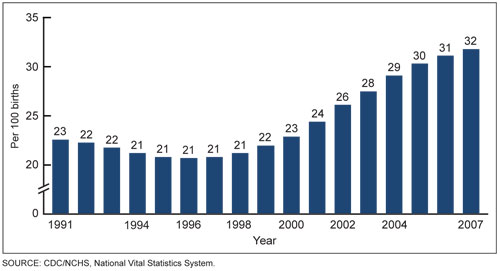

Figure 2. Increasing Rates of Cesarean Section, 1991 to 2007. Data from the US Department of Health and Human Services.

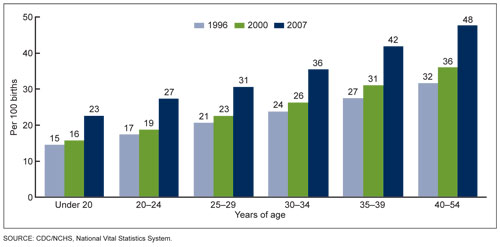

Figure 3. Cesarean delivery rates by age of mother. United States, 1998, 2000 & 2007. Data from the US Department of Health and Human Services.

In March 2010, the National Institutes of Health (NIH) hosted its Consensus Development Conference on the subject of VBAC and concluded, "Given the available evidence, trial of labor is a reasonable option for many pregnant women with one prior low transverse uterine incision.".

Also in March 2010, the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS), Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) reported that VBAC is a reasonable and safe choice for the majority of women with a history of prior C/S and that there is emerging evidence of serious harm relating to multiple Cesarean Sections.

In July 2010, The American Congress of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) similarly revised their own guidelines to be less restrictive of VBAC, stating, "Attempting a vaginal birth after cesarean (VBAC) is a safe and appropriate choice for most women who have had a prior cesarean delivery, including for some women who have had two previous cesareans."

In order to understand the overall risks of rupture, it is important to consider a number of variables regarding the risk of rupture in the following cases:

The general consensus is that the risk of uterine rupture increases as the number of previous C/S increases; however, the overall risk appears to be within the absolute risk range of a single C/S.

Studies suggest that the risk of uterine rupture is between 0.47%- 1% for previous C/S x1. For women who have had multiple C/S: Landon et al. (2006) suggest the risk of rupture rises to 0.9%. Fitzpatrick et al. (2012) also found a slight increase in risk for women how had had 2 or more previous C/S. However Cahill et al. (2010) found that:

The risk of the death of the mother (maternal mortality) associated with uterine rupture is low.

Women attempting a TOLAC, regardless of the final route of delivery, are at decreased risk of maternal mortality compared to elective repeat cesarean section.

In fact, when factoring out the risk of maternal death associated with pregnancy itself and with ERCS, the risk of death from a TOLAC is approximately half that of ERCS (4:100,000 vs. 13:100,000).

Further, the NIH Consensus study failed to report any maternal deaths specifically associated with uterine rupture.

Studies of fetal mortality (deaths in utero at 20 weeks of gestation or greater) suggest a higher death rate in TOLAC at 50 to 130 per 100,000 compared to ERCS at 0 to 40 per 100,000. ERCS may have contributed to the reduction of stillbirths that occur in the late third trimester and the decline in perinatal mortality observed over the last two decades because ERCS is rarely performed after 40 weeks whereas women who undergo TOLAC may have longer gestations.

Studies of perinatal mortality (death between 20 weeks of gestation and 28 days of life) show that the perinatal mortality rate is increased for TOLAC (130 per 100,000) compared to ERCS at 50 per 100,000. Although this difference is statistically significant, the magnitude of the difference between the two groups is small and comparable to the perinatal mortality rate observed among laboring nulliparous women.

The neonatal mortality rate (death in the first 28 days of life) is 110 per 100,000 for TOLAC compared to 50 per 100,000 for ERCS.

Guise et al (2004) performed a systematic review of research concerning VBAC and uterine rupture. They found that uterine rupture resulted in: 0 maternal deaths; 5% perinatal deaths (baby); and 13% hysterectomy. They conclude that:

"Although the literature on uterine rupture is imprecise and inconsistent, existing studies indicate that 370 (213 to 1370) elective caesarean deliveries would need to be performed to prevent one symptomatic uterine rupture."

The overall risk of fetal death during TOLAC is approximately 20:100,000 TOLACs or 1/5000. For term pregnancies, the reported risk of fetal death with uterine rupture is less than 3%.

The risk of hysterectomy (Cesarean Hysterectomy, C-Hyst) is lower with TOLAC compared to ERCS (157 versus 280 per 100,000 respectively) and may be lower in women at term. However, when a uterine rupture occurs, the percentage of women requiring C-Hyst is between 14-33%.

Limited evidence suggests that the risk of C-Hyst increases with induction of labor, high-risk pregnancy, and increasing number of cesarean deliveries:

There is an association between C/S delivery and abnormal placental position and growth in subsequent pregnancies. This risk begins following the first C/S and increases with each subsequent C/S, especially after 4 C/S. Therefore, it is important to consider this risk in women wanting to have large families.

The incidence of placenta previa (placenta covering the cervix) significantly increases in women with each additional C/S delivery:

The presence of placenta previa is also associated with an increased incidence of placenta accreta, increta, and percreta.

Under normal circumstances, the placenta attaches to the uterine wall in the upper portion of the uterus (fundus) and it does so like a suction cup without deeply penetrating into the uterine tissue or muscle. Placenta Accreta, Increta and Percreta are all abnormal and potentially life threatening attachments of the placenta into muscle and sometimes through the entire uterine wall to include adjacent organs such as the bladder and rectum.

Placenta accreta is an invasion of the myometrium which does not penetrate the entire thickness of the uterine muscle. It is the most common form of the condition and accounts for 75-78% of cases.

Placenta increta occurs when the placenta further extends into the myometrium, penetrating deeper into the muscle. This represents 17% of cases.

Placenta percreta represents the worst of this condition, when the placenta penetrates the entire myometrium through the entire uterine wall. This variant can lead to the placenta attaching to other organs such as the rectum or bladder. This represents 5-7% of cases.

Infants born by ERCS are at increased risk for birth trauma such as fetal lacerations caused by the surgical knife used to make the C/S incision.

However, brachial plexus injuries are more common with VBAC as compared to ERCS. The brachial plexus is a network of nerves originating in the spinal cord, and innervating to the shoulder, arm and hand. Brachial plexus injuries are caused by damage to those nerves.

Injury to this area it most commonly associated with shoulder dystocia, an impaction of the infant's shoulder behind the maternal symphysis pubis (pubic bone). The lateral traction on the head, as part of the corrective maneuvers to deliver the infant during a shoulder dystocia, stretches the brachial plexus, leading to injury 4%-40% of the time.

Studies of brachial plexus injury show an overall risk of between 1:2500 to 1:250 live births. An incidence of brachial plexus injury in infants born by VBAC is 1.8:1,000 compared to 3:10,000 among infants born by ERCS.

Therefore, the risk of brachial plexus injuries during VBAC is no greater than that of normal vaginal deliveries, but greater than in ERCS.

A commonly stated reason to perform either an elective Cesarean Section or Elective Repeat Cesarean (ERCS) is to avoid potential fetal brain injury or birth trauma from a delivery through the birth canal.

One of the most severe forms of brain injury, called Celebral Palsy (CP), was at one time thought to be most commonly associated with a vaginal delivery; however, a review of the most recent medical data demonstrates that the causes of CP are multi-factorial with fewer than 10% specifically associated with birth trauma.

Celebral Palsy is an broad term which includes a group of permanent, non-progressive, non-contagious motor conditions that cause physical disability in human brain function, most commonly seen by defects in body movement and control. Cerebral refers to the cerebrum, which is the affected area of the brain (although the disorder most likely involves problems with the connection between the cortex and other parts of the brain such as the cerebellum), and Palsy which refers to a disorder of movement.

CP occurs in approximately 1/500 live births. There is no known cure for this condition and medical management is limited to the prevention and treatment of complications arising from the effects of CP.

CP is caused by damage to the motor control centers of the developing brain and can occur during pregnancy, during childbirth or after birth up to about age three. These effects cause problems in movement and posture cause activity and are often accompanied by disturbances of cognitive reasoning, speech and communication, sensation, depth perception, and other sight-based perceptual problems.

Approximately one third of children also suffer from epilepsy.

Based on the current data, neither an elective Cesarean Section nor an ERCS is recommended to specifically reduce the risk of CP. Further, there is no consensus of data that the risk of CP is increased by attempting a VBAC or that ERCS is significantly safer than VBAC in reducing the risk of CP.

There is a limited amount of evidence to suggest that becoming pregnant shortly after having a C/S increases the risk of uterine rupture in the subsequent pregnancy. There are generally three intervals of time with decreasing risk of uterine rupture associated with each group.

An interval of pregnancy of less than 6 months since the previous C/S delivery appears to be associated with the highest risk of uterine rupture.

An interval of between 6 months to 2 years appears to have the next lowest risk of uterine rupture.

And an interval of greater than 2 years appears to have the lowest risk of uterine rupture.

Stamilio (2007), in a study involving 286 women who got pregnant within 6 month of their C/S had a uterine rupture rate of 3.05% as compared to 0.9% (3x higher). Stamiliio stated,

"We hypothesized that short interpregnancy intervals may lead to altered wound healing and an increased risk of uterine rupture in patients who attempt a vaginal birth after cesarean. Our hypothesis is based on previous observational studies that suggest an association between short birth interval and increased adverse perinatal outcomes and wound-healing research that indicates that uterine smooth muscle tissue repair evolves over several months... Importantly, there is radiographic and hysteroscopic evidence that cesarean scar development is incomplete as long as 6 or 12 months postoperatively."

Bujold E, Gauthier RJ (2010), in a studiy of 1768 women, found a uterine rupture rate of 1.3% for interdelivery period of 24 months or longer, 1.9% for interdelivery periods between 18-23 months and 4.8% for interdelivery period of less than 18 months.

Based on this limited data, it is recommended that a patient wait 2 years between a previous C/S and the next pregnancy in order to keep the risk of uterine rupture below 1%. If a patient were to become pregnant less than 6 months, with her last delivery being by C/S, she should be counseled that her risks of uterine rupture are between 1-5% and a ERCS over VBAC should be considered. However, there are no specific contraindications to attempting a VBAC.

The following recommendations are based on Dr. Novoa's 30 years of experience having assisted in over 500 VBACs (Including Previous C/S x 2,3,4) with a VBAC Success Rate at an estimated 90% with no maternal or fetal morbidity or mortality.

When possible, ask your doctor what is their VBAC Success Rate. The national average is approximately 70%.

Elective inductions have a relatively high failure rate. Elective VBAC inductions can significantly increase your risk of failure or scare your doctor into a premature stoppage of a TOLAC leading to unnecessary Cesarean Section.

Spontaneous Labor with unassisted progress and Spontaneous rupture of membranes is safer than induction by any method to include AROM, Foley bulb or Pitocin. Misoprostol is contraindicated.

The LUST may be the single most important factor in avoiding a Uterine Rupture.

The thicker, the better. A thickness of 3mm or greater is optimal. A thickness less then than 2mm is suboptimal or generally not recommended to attempt a TOLAC due to higher risk of uterine rupture.

The thickness should be measured by ultrasound a few days before labor or during early labor.

A HORIZONTAL lower uterine segment is optimal.

A lower VERTICAL incision is acceptable. A HIGH VERTICAL, "CLASSICAL", Previous Uterine surgeries penetrating through the myometrium is subtotal and generally not recommended.

An Epidural catheter should be placed upon admission. Medication can be gauged by how much the patient wants to feel. It is also prevents any delay with anesthesia in case of a STAT Cesarean section.

An Intrauterine Pressure Catheter or IUPC can be beneficial in determining the intensity of natural vs artificially induced contractions calculated by Montevideo units. While an IUPC may not predict or confirm an Uterine Rupture, it can objectively document a change in the contraction pattern or show early intrauterine bleeding with backflow into the catheter.

If you have a life-threatening emergency, call 911. If your matter is an emergency (only) and you need to speak to Dr. Novoa concerning this emergency after the office has closed, please call 951.595.9944 (Wait for the prompt and you will be connected to Dr. Novoa). If you have a question that is not an immediate emergency, please call during office hours. A nurse or physician will assist you as soon as possible.

915.595.9944

915.996.9074

Monday - Friday:

9:00am - 5:00pm